Part 1: The Cinematographer’s Paradox

Why I Don’t Believe in Weddings (But Film Them Anyway)

The groom's family stood in a nervous line on the Cabramatta street, each person clutching a red lacquer tray…

…That's when it hit me: I wasn't just documenting their wedding—I was directing the last performance of a dying tradition.

The groom’s family stood in a nervous line on the Cabramatta street, each person clutching a red lacquer tray laden with traditional gifts. It was 2023, and Jessica’s wedding day was about to begin with the lễ ăn hỏi—the formal presentation of betrothal gifts that Vietnamese families had performed for centuries. But something was wrong.

Eight mâm quả trays filled with betel leaves, tea, wine, and ceremonial cakes sat heavy in their hands. The bride’s female relatives clustered uncertainly by the front door, whispering among themselves in English.

“Who’s supposed to receive what?” the bride’s aunt asked nervously. “And do we inspect them first or just take them?”

The grandmother—keeper of the ritual—had passed away eight months earlier. Now three generations of Australian-Vietnamese family looked to me, a white Greek-Australian cinematographer, for guidance on their own cultural ceremony.

I knew the protocol. Which gifts went to which relatives, how the formal handoff should proceed, even the specific order for presenting the blessing money. After filming dozens of Vietnamese weddings, I’d memorized traditions that this family was losing in real time.

“The eldest lady receives the first tray,” I said quietly, lowering my camera. “She inspects the contents, accepts the lì xì envelope, then passes it to the others. Only then can the groom’s party enter the house.”

They nodded gratefully and formed two parallel lines—groom’s family with their offerings, bride’s representatives ready to receive them. Through my viewfinder, I watched them perform rituals they half-remembered, guided by someone who’d learned their culture secondhand.

But here’s what struck me: they weren’t trying to recreate their grandparents’ wedding exactly. They were choosing which elements felt meaningful and which felt outdated. The tea ceremony happened, but shortened. The formal gift exchange continued, but with English explanations for Australian relatives. This wasn’t cultural preservation—it was conscious cultural evolution.

What mattered most wasn’t perfect adherence to tradition but the intentional connection between two families uniting across continents and generations. Yet here we were, fixated on whether I’d captured the ceremonial handoff correctly.

That’s when it hit me: I wasn’t just documenting their wedding—I was directing the last performance of a dying tradition.

The Confession

Here’s something I tell couples when they ask about my own wedding: I don’t believe in weddings. At 56, I’ve been in a de facto relationship for years. When people push for details, I joke that marriage just isn’t my thing.

But that’s only half true.

The full truth is messier, like everything about social change. I’m a wedding cinematographer who runs CineMotive, where my team of eight films over 100 weddings annually. I spend my days documenting society’s most traditional institution while personally avoiding it. I crave the very traditions I watch disappearing through my lens. I hate attention and ceremony, yet I’ve built a career around exactly what I avoid.

This contradiction isn’t a bug in my personality—it’s the feature that makes me good at what I do. I see the gap between what weddings promise and what they deliver because I’m simultaneously inside and outside the system.

Born in Canterbury Hospital, Sydney in 1969 to Greek Orthodox parents who came to Australia with literally nothing, I grew up believing tradition was sacred and certainty was comfort. My childhood was midnight Easter masses, forty-day Lenten fasts, and knowing exactly where you belonged in the family hierarchy.

Now? I attend none of those services. I barely fast. I’m part of the very cultural dilution I spend my days documenting. And watching myself fade has taught me to recognise the same pattern in every family I film.

The Moments That Changed Everything

The Watchers in the Shadows

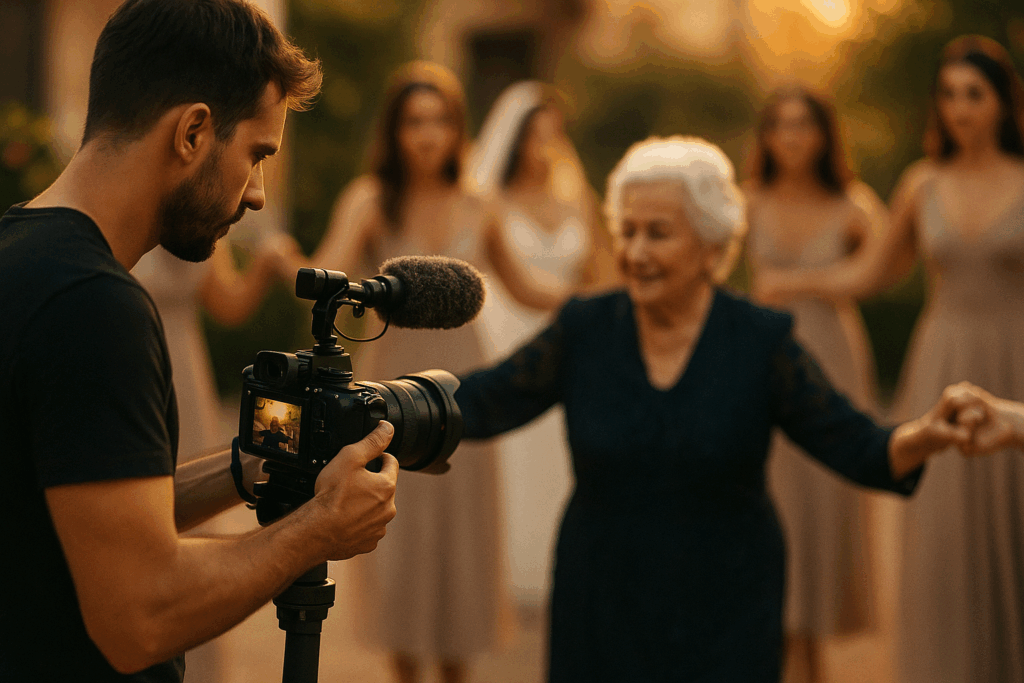

At every reception, I see them: grandparents and elderly aunties sitting alone in the dimly lit corners, faces turned toward the dance floor with distant, unreadable expressions. They watch their grandchildren attempt traditional dances to Western beats, their conservative dark clothing a stark contrast to the sequined dresses and loosened ties swirling past them.

Last month at a Greek wedding in Marrickville, I noticed Yiayia Sophia at table twelve, hands folded, watching her granddaughter’s friends stumble through the kalamatiano. The bride wore a strapless gown that would have scandalized her grandmother’s generation. The music was too loud, the steps too fast, the reverence completely absent. But Yiayia Sophia just watched, her eyes holding decades of memory—real village celebrations where the whole community knew the songs, where modesty mattered, where tradition lived in people’s bones instead of requiring YouTube tutorials.

I wanted to sit beside her. To turn on my microphone and ask what she was thinking. To capture her stories about weddings in the old country, her wisdom about marriage, her memories of when these dances meant something beyond photo opportunities. I imagined surprising the couple in their final edit with audio of their yiayia sharing blessings they’d never heard, advice they’d never thought to ask for, stories that would disappear with her.

But I was too busy chasing the timeline. The bouquet toss was starting. The couple needed their sunset portraits. The golden hour wouldn’t wait for an old woman’s reflections.

Every Wedding Now: When Content Comes First

It’s 11 AM in the master bedroom of a Maroubra house. The bride sits in her silk robe while her bridesmaids, still in matching pajamas, pop champagne for the mandatory “getting ready” shots. We’ve spent ninety minutes on detail photography—rings arranged with perfume bottles, shoes styled against invitation suites, flat lays that will look identical to every other wedding on Instagram.

The maid of honor holds up her phone. “Can we do that TikTok transition now? You know, where you throw the robe and appear in the dress?”

I’m adjusting lighting for the fifteenth variation of the same champagne toast when there’s a soft knock on the door.

“Yiayia is downstairs,” the bride’s cousin whispers. “She wants to see you before the ceremony.”

The bride glances at her timeline, printed and laminated. “Can she wait? We still need to do dad’s first look, my solo portraits, and the bridesmaids reveal video. Tell her I’ll see her when I’m dressed.”

I watch the cousin disappear down the hallway to tell an 89-year-old grandmother to wait. Yiayia has been awake since 5 AM, dressed in her best black dress, probably sitting alone downstairs in the living room clutching her small purse, just wanting to bless her granddaughter before the ceremony begins.

But the timeline says no. First we need thirty minutes of bridal portraits, twenty minutes for dad’s reaction shots, fifteen minutes for the bridesmaids’ choreographed reveal. Content creation comes first. Connection comes later.

By the time we finish our shot list two hours later, Yiayia has been waiting downstairs for over an hour. When the bride finally appears in full dress and makeup, her grandmother’s eyes fill with tears—pure joy mixed with something deeper, a recognition that this moment she’d been waiting for was finally here.

Watching that emotion in her weathered face, I realized what I should have done. The moment that cousin whispered “Yiayia wants to see you,” I should have said, “Bring her up now. Let’s capture that private moment between just the two of them first.”

I could have filmed the grandmother’s blessing before the chaos of timelines and shot lists. A quiet moment of just bride and yiayia, maybe her adjusting the veil or sharing whispered advice in Greek. Then we could have done all the other content afterward.

Instead, I watched that precious reaction happen once, knowing we’d missed an hour of opportunities for intimate moments like this. That’s when I realized: throughout the entire day, grandma should be the priority, not the afterthought. Those emotional moments I was witnessing were exactly what we should be creating more of, not scheduling around.

The Epiphany Wedding, 2023

A couple spent their entire cocktail hour taking portraits while their 150 guests mingled awkwardly without them. Cocktail time is supposed to be when newlyweds finally get to relax and connect with everyone who came to celebrate them—the cousins who flew from interstate, the childhood friends, the elderly relatives who might not stay late.

“But if we mingle now, the guests will see us before our grand entrance,” couples often tell me.

I gently remind them: “They already saw you at the ceremony. There’s nothing left to hide.”

“Oh yeah, true. Of course they have,” they usually respond, as if the wedding industry has convinced them to forget their own ceremony happened.

Cocktail hour is precious because it’s often the only opportunity for real one-on-one time with guests. During the reception, couples get maybe thirty seconds per table between speeches, dancing, and cake cutting. But during cocktails? That’s when meaningful conversations happen, when stories get shared, when connections deepen.

Instead of mingling, I watched guests nursing their drinks, checking their watches, wondering when they’d actually get to congratulate the couple. The 90-year-old grandmother sat alone at her table, clutching her small purse, while we chased golden hour lighting in the gardens. Extended family members who hadn’t seen the bride in years stood around making small talk with strangers.

When the couple finally returned from portraits, guests had already been seated at their designated reception tables, waiting for the official program to begin. The couple had maybe ten minutes to say quick hellos before being shuffled off to their bridal suite for touch-ups and soothing drinks before the grand entrance.

The bride managed a hurried hug with her yiayia, a brief wave to her university friends, a rushed thank-you to the relatives who’d traveled interstate. Then it was time to disappear again for final preparations. Conversations that should have happened over canapés never happened at all.

That’s when I realized: I wasn’t documenting a wedding—I was directing a photo shoot that happened to include a wedding. We’d stolen the couple’s only unstructured time with their loved ones and replaced it with staged moments they’d view later instead of real connections they could experience now.

We’re hired to capture memories, but our timelines sometimes prevent them from forming. You can’t document authentic celebration if the couple never gets the chance to actually celebrate with their people.

But how did we get here? When did weddings become performance pieces instead of celebrations?